The European elections in May left a scenario in which, for the first time, the Social and Christian-democratic parties do not have an absolute majority in the European Parliament. This fact will have a decisive influence on parliamentary arithmetics, since the forces that have dominated European politics so far (European People’s Party and the Party of European Socialists) will require a third pro-European parties (Liberal or Ecologists) to be able to take forward the legislative agenda marked by the new European Commission. Report by Federico Bonaudi.

The European Parliament asserts its institutional role in European policy-making by exercising these various functions: participation in the legislative process, budgetary and control powers, involvement in treaty revision and its right to intervene before the European Court of Justice. Regarding the legislative process, the European Parliament’s role has progressed from a purely advisory role to co-decision on an equal footing with the Council.

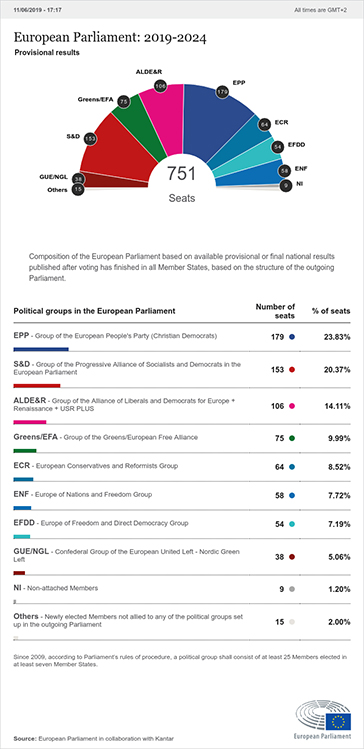

In the ninth election since 1979, Europeans chose to renew the 751 members of the European Parliament for the 2019-2024 term. After the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, the number of MEPs will be reduced to 705.

In the ninth election since 1979, Europeans chose to renew the 751 members of the European Parliament for the 2019-2024 term. After the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, the number of MEPs will be reduced to 705.

After the elections and according to the official information provided so far, this is the new face of the European Parliament for the 9th term:

So what did we learn?

• Europe matters. There was a higher turn-out compared to previous elections. The democratic legitimacy of the EU is reinforced, due to the highest turnout of voters in 25 years and the fact that 75% of voters still chose pro-European parties.

• The EU has resisted the assault of the extreme right and Europhobic forces thanks to the rise of liberals and greens. The European People’s Party (EPP) and the Socialists (S&D) have lost the absolute majority that they have had for 40 years and will need support to contain the Eurosceptic parties that have performed well in Member States providing an important number of MEPs like France, Italy, the United Kingdom or Poland.

• Traditional parties (EPP and S&D) lost substantial ground to a variety of new-comers: they lost to the centrist liberal-democrats, to the leftist greens and to right-wing conservatives. The EPP is now in a weaker position – especially as S&D, ALDE and the Greens are keen to challenge its leadership in the EU institutions.

• There was a substantial increase in the seats of the ALDE-Renaissance group (liberal-democrats). Not (just) because it gained substantially in absolute numbers, but because its position has become vital for making any sort of coalition.

• The smaller-than-expected gap between the EPP and S&D (combined with poor results of both) will make it harder for EPP to push through their (initial) candidate for the Presidency of the Commission.

• EPP and S&D remain the strongest groups mainly because of the smaller countries. From among the big Member States, these two traditional forces have won only in Germany (EPP) and Spain (PES/S&D). They had big losses in France, Italy, Poland (in the case of EPP), and in Germany, UK and France (in the case of the socialists). The S&D will be, nevertheless, stronger than forecast thanks to their good results in Spain and Italy.

• EPP manages to edge the Socialists thanks to its Central Eastern European strongholds.

• The smaller EPP-S&D gap will also make it even harder for the EPP to lose any of their members, ie. FIDESZ, who scored very high in Hungary and would be EPP’s third largest national party delegation.

• The rise of Eurosceptic forces has been mitigated in some countries (Germany) and neutralised in others (Holland and Austria), thanks, in part, to a participation that has soared for the first time in 40 years of parliamentary elections European. But the four days of voting have unleashed a political shake-up of important dimensions, with a European Parliament without sharp majorities and with several weakened governments like Germany.

• The next European Parliament will be more fragmented than ever and, in legislative practice, coalitions will continue to be made on an issue-by-issue basis. Majorities will be smaller and the votes of a few MEPs will make the difference. This reflects an EU which is increasingly divided and will thus be more difficult to steer and govern. The tensions between Member States that have already emerged over the designation of the new President of the European Commission are illustrative of that.

• Similarly, the impossibility of a grand coalition can have unforeseen effects on the power sharing that happens after each election.

• Three main subjects will be on the agenda of the legislators in the 2019-2024 term: sustainability & climate change, social issues and digitalisation & innovation. In particular, taxing aviation is now high on the agenda of most of the European parties and of the candidates for the role of President of the European Commission.

• A very tough negotiation between the European Parliament and the Member States is currently under way to appoint the President of the European Commission, the President of the European Parliament, the President of the European Central Bank and the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

European elections 2019: inside the Plenary chamber in the European Parliament. Three main subjects will be on the agenda of the legislators in the 2019-2024 term: sustainability & climate change, social issues and digitalisation & innovation. Source: EP/Didier Bauweraerts

ACI EUROPE and the European Parliament

As part of our advocacy efforts to defend our members’ interests, we have traditionally engaged with the European Parliament. So far the different parliamentary committees have been receptive to our main messages thanks to a long-lasting relationship of mutual trust.

After the elections, only 37% of the members of the European Parliament were re-elected. This means that, besides continuing our work with our core of contacts, important educational efforts will need to be made with the 63% of them seating for the first time. An immensely challenging Parliamentary term is ahead, and ACI EUROPE is ready to make its contribution to the agenda.