Airport investment is the key driver of both charges and the delivery of facilities & services. It is also the underlying force that indelibly links charges and delivery. This means that there is an inherent trade-off between low charges on the one hand, and sufficient capacity & quality on the other.

Last year was a busy, tumultuous one in European aeropolitical affairs. The European Commission opened a consultation in advance of developing its Aviation Strategy and then refined and released the final result in December. Then at the end of January this year – nearly 2 months after the launch of the strategy, a new airline association presented itself, made some sensationalist accusations about airport charges and called for more airport regulation. ACI EUROPE’s Economics Manager Donagh Cagney reports on what happened next.

In December of 2015, the European Commission launched its eagerly-anticipated Aviation Strategy.

The Strategy sets out clear policy objectives for the European aviation sector as a whole, with specific consideration given to the contribution that Europe’s airports should make. In particular the Strategy recognises the increasing importance of the ‘quality, efficiency and cost of these (airport) services … to the competitiveness of the industry’, with a particular focus on the importance of both air connectivity and the related looming airport capacity crunch in Europe. The Strategy also gives some guidance as to how airport charges should be regulated in the future, noting that ‘when airports are subject to effective competition, the market should determine the level of airport charges and there is no need for regulation’.

ACI EUROPE took a wider look at the overall performance of the top 21 airports in Europe over the past 10 years. ACI EUROPE’s research encompassed not only their charges, but also developments in capacity, connectivity, service quality and investment at the 21 airports in question.

No sooner had the Strategy been published than ACI EUROPE was presented with the opportunity to reflect on what all this meant in practical terms, for Europe’s largest airports. In January 2016, new airline association Airlines for Europe (A4E) released a report which argued that passengers were being ‘fleeced’ by airports, claiming that charges at the largest 21 airports in the EU & EFTA had increased by +80% over the past decade. A4E argued that this justified more economic regulation of European airports.

As soon as A4E published its figures, it became clear that something was amiss. Several airport members contacted ACI EUROPE, as they could not reconcile A4E’s numbers with their own financial records. But rather than just correct the headline figures, ACI EUROPE instead took a wider look at the overall performance of these airports over the past 10 years. ACI EUROPE’s research encompassed not only their charges, but also developments in capacity, connectivity, service quality and investment at the 21 airports in question.

As well as shedding new light on airports’ delivery on the priorities of the new Aviation Strategy, this approach also allowed insight into the overall value delivered by these airports to their passenger and airline clients. Value was not considered in A4E’s report.

The analysis revealed that over the past decade, Europe’s largest airports delivered additional capacity to handle more than 175 million passengers per annum – the equivalent of adding an additional Heathrow, Charles de Gaulle AND Orly airports to the European aviation network. And annual passenger traffic through these airports subsequently increased by 168 million passengers across the 21 airports – an almost perfect match with the increased capacity provided.

This helped direct connectivity to increase by +11% at these airports, while overall airport connectivity (which includes indirect connections) increased by +52%.

Via ACI’s ‘Airport Service Quality Programme’ passengers reported a level of overall satisfaction that was +12.4% higher at the end of the period compared to the start. Passenger satisfaction scores for a range of different services (such as security waiting times, courtesy & helpfulness of airport staff, terminal cleanliness, etc.) also saw similar increases.

These improvements across the industry were driven by an investment of more than €53 billion which was ploughed back into infrastructure during the last 10 years.

This last finding was of pivotal importance. Improvements in capacity and quality are not delivered out of thin air. Rather, they are driven by significant volumes of investment. And these investments in turn have to be paid for by the users that benefit from those delivered services and facilities – EU State aid rules all but rule out any public funding for larger European airports.

As a result average charges at these airports increased over the period by 25.4% in real terms. In practice, this meant that the additional capacity and quality was delivered for less than €3 per passenger. During this time, charges never covered more than 60-70% of total airport costs, and airport charges actually decreased, as a % of overall airline costs.

Most importantly, the increases in charges occurred where they were needed. Those airports that increased charges also invested twice as much into airport infrastructure, compared to their peers that kept stable or decreased charges. Consequently they also increased both capacity and service quality by twice as much.

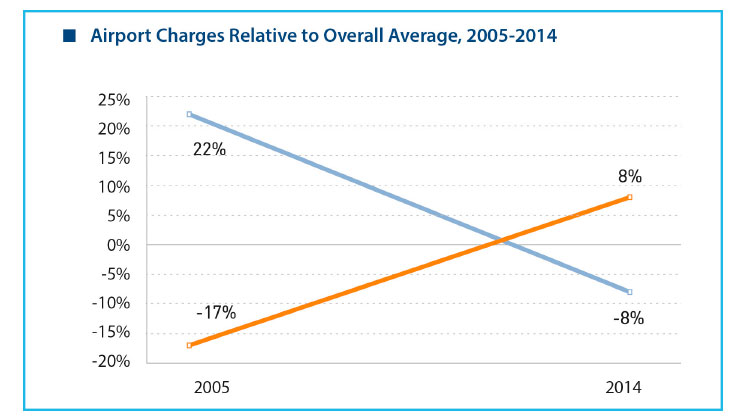

The analysis also shows that those airports that increased charges had previously been significantly cheaper than their peers a decade ago. This is no coincidence. These airports had to invest to bring their facilities & service up to industry standard, and this naturally came at a cost. Meanwhile their peers were benefiting from investment that had already been made, and were therefore able to reduce or keep stable charges across the period.

Airport investment is the key driver of both charges and the delivery of facilities & services. It is also the underlying force that indelibly links charges and delivery. This means that there is an inherent trade-off between low charges on the one hand, and sufficient capacity & quality on the other.

No degree of regulation can escape this fundamental reality. That being said, regulation – if done incorrectly – can make it more difficult to find best trade-off between the two objectives.

Looking across the 21 airports, it became apparent that those airports where charges had increased the most were also those where there was typically most regulatory intervention. The politicisation of airport charges in these jurisdictions meant that difficult decisions were postponed, leading to excessive sweating of assets, unsustainably low charges and larger and more expensive investment projects to remedy the situation. This subsequently led to more sudden and dramatic changes in airport charges. In contrast, those airports that operated within more proportionate regulatory frameworks were more empowered to smooth the profile of charges, and limit the impact of necessary investments.

The finding undermines A4E calls for tighter regulation of airports, which had been made specifically on the grounds of dramatic changes in airport charges. Even if the claimed 80% figure had been correct, A4E’s proposed policy responses would still have been self-defeating.

Looking ahead, there are reasons to be cheerful about the policy framework facing European airports. The EU’s Aviation Strategy does set high standards for the industry. But it does so as part of a wider vision that is both coherent and joined up. While setting demanding objectives, the Strategy also recognises that regulatory intervention should be limited only to where it is demonstrably needed. And if turned into practice, this principle will allow airports to be empowered to make precisely those investments that are needed, to attain the Strategy’s wider goals.